The Ethics of Money Production

Sunday, 16 February 2020 · 36 min read · economics

This is an abridged version of Jörg Guido Hülsmann’s The Ethics of Money Production, with an emphasis on the origins of money, private coinage, and competition of private currencies.

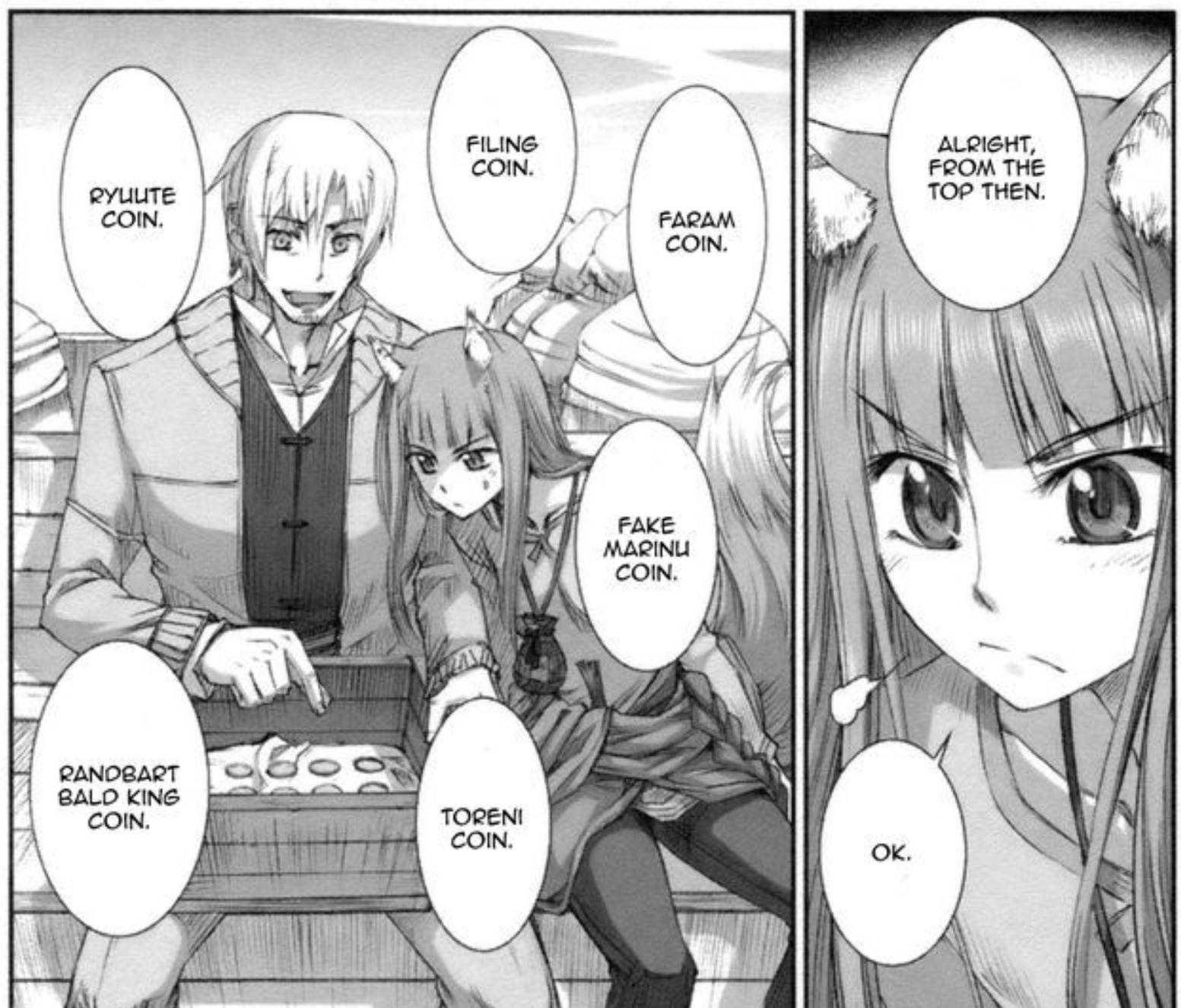

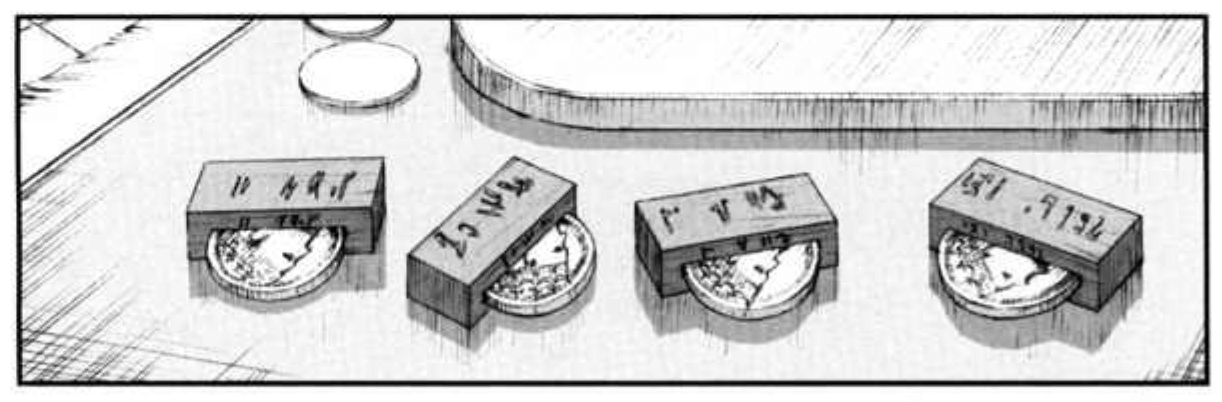

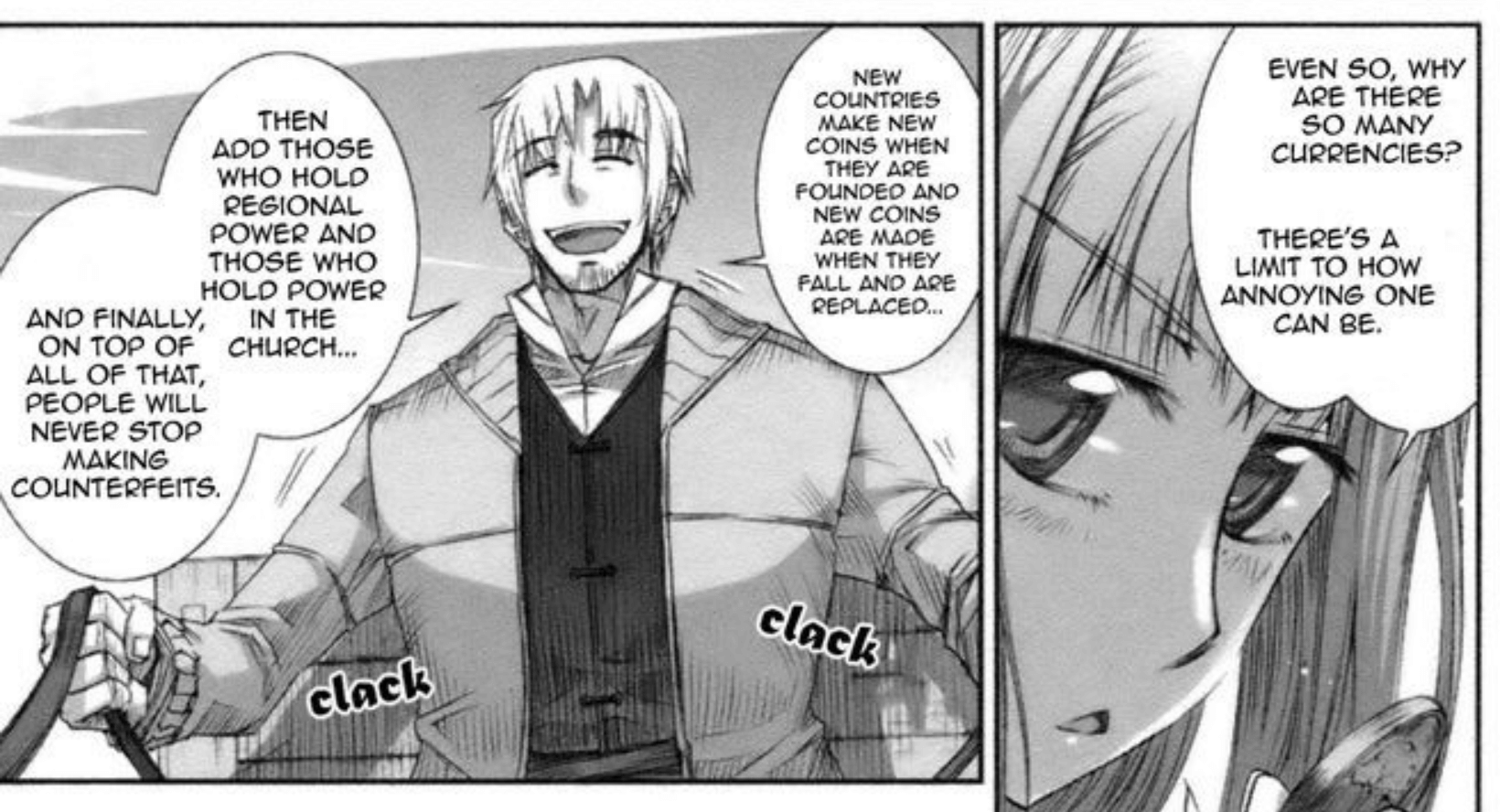

The original book is available as a free PDF and on paperback. Images used are from Spice and Wolf by Keito Koume and Isuna Hasekura.

📬 Get updates straight to your inbox.

Subscribe to my newsletter so you don't miss new content.

Division of Labour without Money

The fundamental law of economics is that joint production yields a greater return than isolated production. Two individuals working in isolation from one another produce less physical goods and services than if they coordinated their efforts.

In a world without money, people would exchange their products in barter. For example, Jones would barter his apple against two eggs from Brown. In such a world, the volume of exchanges—in other words, the extent of social cooperation—is limited through technological constraints and the problem of the double coincidence of wants.

Barter exchanges take place only if each trading partner has a direct personal need for the good he receives in the exchange. But even in those cases in which the double coincidence of wants is given, the goods are often too bulky and cannot be subdivided to accommodate them to the needs.

Imagine a carpenter trying to buy ten pounds of flour with a chair. The chair is far more valuable than the flour, so how can an exchange be arranged? Cutting the chair into, say, twenty pieces would not provide him with objects that are worth just one twentieth of the value of a chair; rather such a “division” of the chair would destroy its entire value. The exchange would therefore not take place.

These problems can be reduced through indirect exchange. In our example, the carpenter could exchange his chair against 20 ounces of silver, and then buy the ten pounds of flour in exchange for a quarter ounce of silver. The result is that the carpenter’s need for flour, which otherwise would have remained unsatisfied, is now satisfied through an additional exchange and the use of a medium of exchange.

Thus indirect exchange provides our carpenter with additional opportunities for cooperation with other human beings. It contributes to the material and spiritual advancement of each person.

How Commodities turn into Money

How does a commodity such as gold or silver turn into money? This happens through a gradual process in the course of which more and more market participants, each by themselves, gravitate to gold and silver rather than other commodities in their indirect exchanges.

The historical selection of gold, silver, and copper was not made through some sort of a social contract or convention. Rather, it resulted from the spontaneous convergence of many individual choices, a convergence led by the physical characteristics of precious metals.

For a commodity to be spontaneously adopted as a medium of exchange, it must be desired for its nonmonetary services (for its own use in consumption and production) and be widely bought and sold. The prices that are initially being paid for the commodity’s use allow prospective buyers to estimate the future prices at which one can reasonably expect to resell it. The prices paid for its nonmonetary use are, so to speak, the empirical basis for its use in indirect exchange. It would be extremely risky to buy a commodity for indirect exchange without knowing its past prices!

The spontaneous emergence of a medium of exchange is virtually impossible whenever historical price data is lacking. On the other hand, when it exists, then there can arise a monetary demand (the desire to use it as money) for the commodity in question. The monetary demand then further adds to the commodity’s nonmonetary demand, such that the price of the money-commodity contains a monetary component and a nonmonetary component. Although in a developed economy the former is likely to outweigh the latter quite substantially, it is important to keep in mind that the monetary use of a commodity ultimately depends on its nonmonetary use.

Historical monies derive their value from their use in consumption. Even in the case of the precious metals this is so. It is true that they are not destroyed in consumption, as for example tobacco and cotton, but they are nevertheless consumed as jewelry, ornament, and in a variety of industrial applications.

It was in the very nature of money to be a marketable thing that had its primary use in consumption.

Natural Money

When a medium of exchange is generally accepted in society, it is called “money”. We may call any kind of money that comes into use by the voluntary cooperation of acting persons “natural money”.

Natural money must possess two qualities:

- It must be valuable prior to its monetary use, and

- It must be physically suitable to be used as a medium of exchange.

Still we call them natural monies, not because of their physical characteristics, but because free human beings have spontaneously selected them for that use. In short, one cannot tell on a priori grounds what the natural money of a society is. The only way to find this out is to let people freely associate and choose the best means of exchange out of the available alternatives.

Gold, silver, and copper have been natural monies for several thousand years in many human societies. The natural costs that go in hand with producing gold and silver are in fact a supreme reason why these metals are better monies than paper. The fact that they are costly means that they cannot be multiplied at will.

Coinage

The precious metals would have become monies even if coinage had never been invented, because even in the form of bullion their physical advantages outweigh those of all alternatives. However, coinage added convenience to the benefits derived from indirect exchange, and that convenience contributed to the spreading of monetary exchanges.

Coinage allows the exchange of precious metals without engaging in the labor-intensive processes of weighing the metal and melting it down. One can determine a metal weight by simply counting the coins.

It does so through an imprint, which informs the public of the authenticity of the coin’s weight and fineness in metal content. This is why coin names were typically the names of weights, for example, the pound, the mark, or the franc.

Putting Trust in the Minter

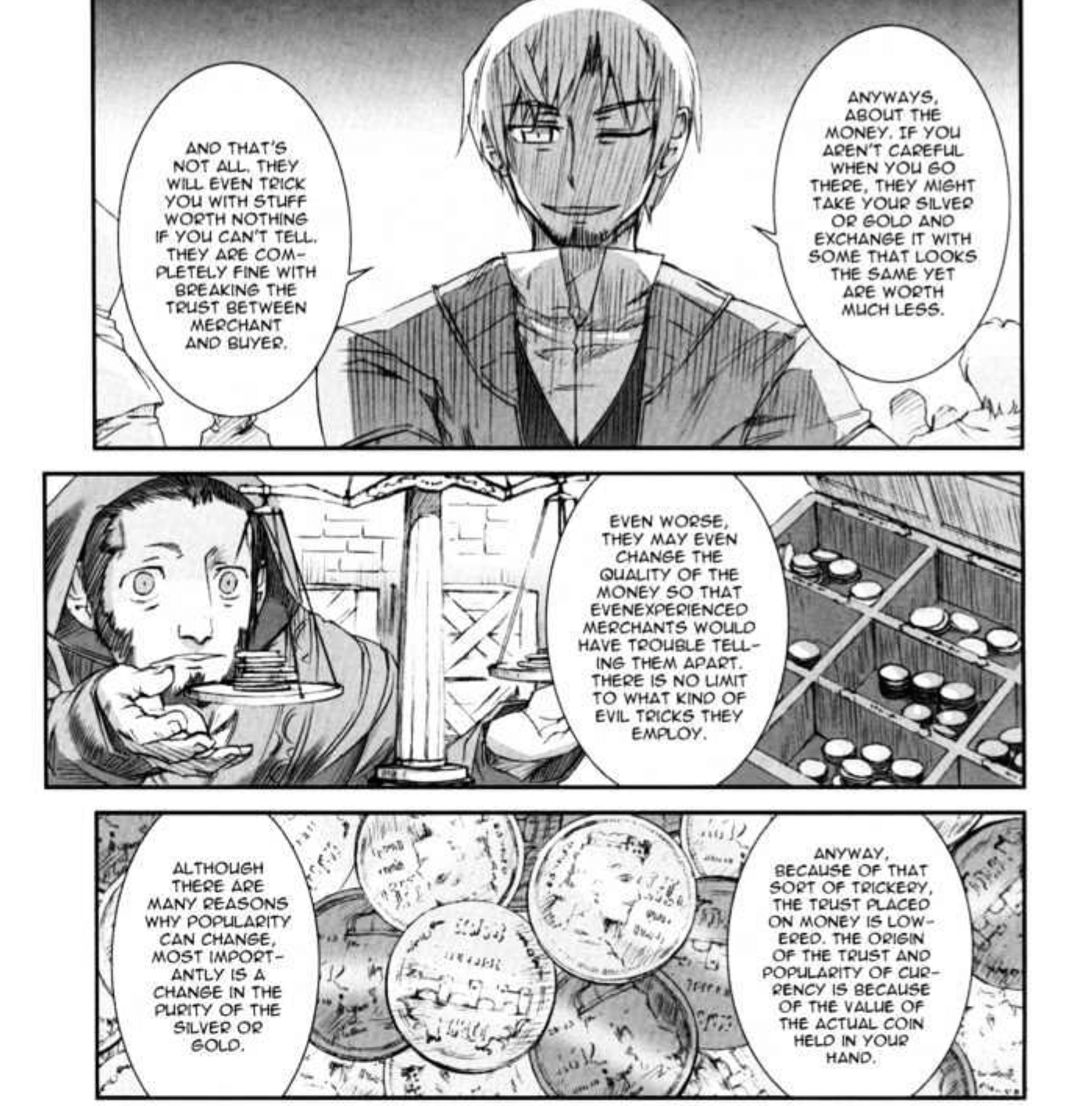

Coinage depends entirely on the trustworthiness of the minter. If the market participants cannot trust the certificate, they will rather do without the coin and go through the extra trouble of weighing the metal and possibly melting it down to determine its content of fine metal.

A trustworthy coin saves you the trouble and thus adds to the value of the bullion contained in the coin; for example, a trustworthy 1-ounce silver coin is more valuable than 1 ounce of silver bullion. People therefore pay higher prices for coins than for bullion, and the minter lives off this price margin.

Because the value of the certificate depends on the trustworthiness of the minter, coins are typically used within limited geographical areas. Only the people who know the minter are likely to accept his coins. All others will insist on being paid in bullion or in coins they trust. This does not mean that in practice every village needs a different set of coins. The geographical radius within which a coin is used can grow very large and it can even become world encompassing if the minter has an excellent reputation.

When Trust Fails

There is a solid historical record documenting how governments have abused the trust that the citizens put into them. There was in fact hardly a government that did not in this way abuse its monopoly of coinage. Ancient Greeks and Romans, medieval princes, dukes and emperors, as well as democratic parliaments have recklessly debased the coins of their country, knowing that the law imposed the bad coins on their subjects at a nominal value determined by the government.

Before the age of banking, debasement had been the standard form of inflation. Debasement is a special way of altering coins made out of precious metal, usually lowering its precious metal content. In the Western world, debasement was the standard form of inflation until the seventeenth century.

A great number of monetary thinkers from the Middle Ages to our times have held that coinage should be entrusted to the princes or governments, who, because they were the natural leaders of society, were also the people to be naturally trusted. The medieval scholastics knew full well that the princes frequently abused this trust, placing for example an imprint of “one ounce” on a coin that contained merely half an ounce, pocketing the other half of an ounce for themselves.

Inflation and Legal-Tender Laws

Long before the age of banking, Nicholas Oresme stressed the scandalous quantitative aspect of inflation protected by legal-tender laws. He postulated that the princes did not have the right to alter the coins at all, unless they had the consent of the entire community, that is, the entire community of money users.

Oresme says:

. . . Again, if the prince has the right to make a simple alteration in the coinage and draw some profit from it, he must also have the right to make a greater alteration and draw more profit, and to do this more than once and make still more. . . . And it is probable that he or his successors would go on doing this either of their own motion or by the advice of their council as soon as this was permitted, because human nature is inclined and prone to heap up riches when it can do so with ease. And so the prince would be at length able to draw to himself almost all the money or riches of his subjects and reduce them to slavery. And this would be tyrannical, indeed true and absolute tyranny, as it is represented by philosophers and in ancient history.

Inflation is an extension of the nominal quantity of any medium of exchange beyond the quantity that would have been produced on the free market. Legal-tender laws eliminate all technical obstacles to an infinite inflation of coins. Any coin, however much it is debased, must be accepted in payment of its full nominal amount. It is therefore possible to debase coins to such an extent that they contain not a trace of precious metal anymore.

Inflation benefits the government that controls it, not only at the expense of the population at large, but also at the expense of all secondary and tertiary governments.

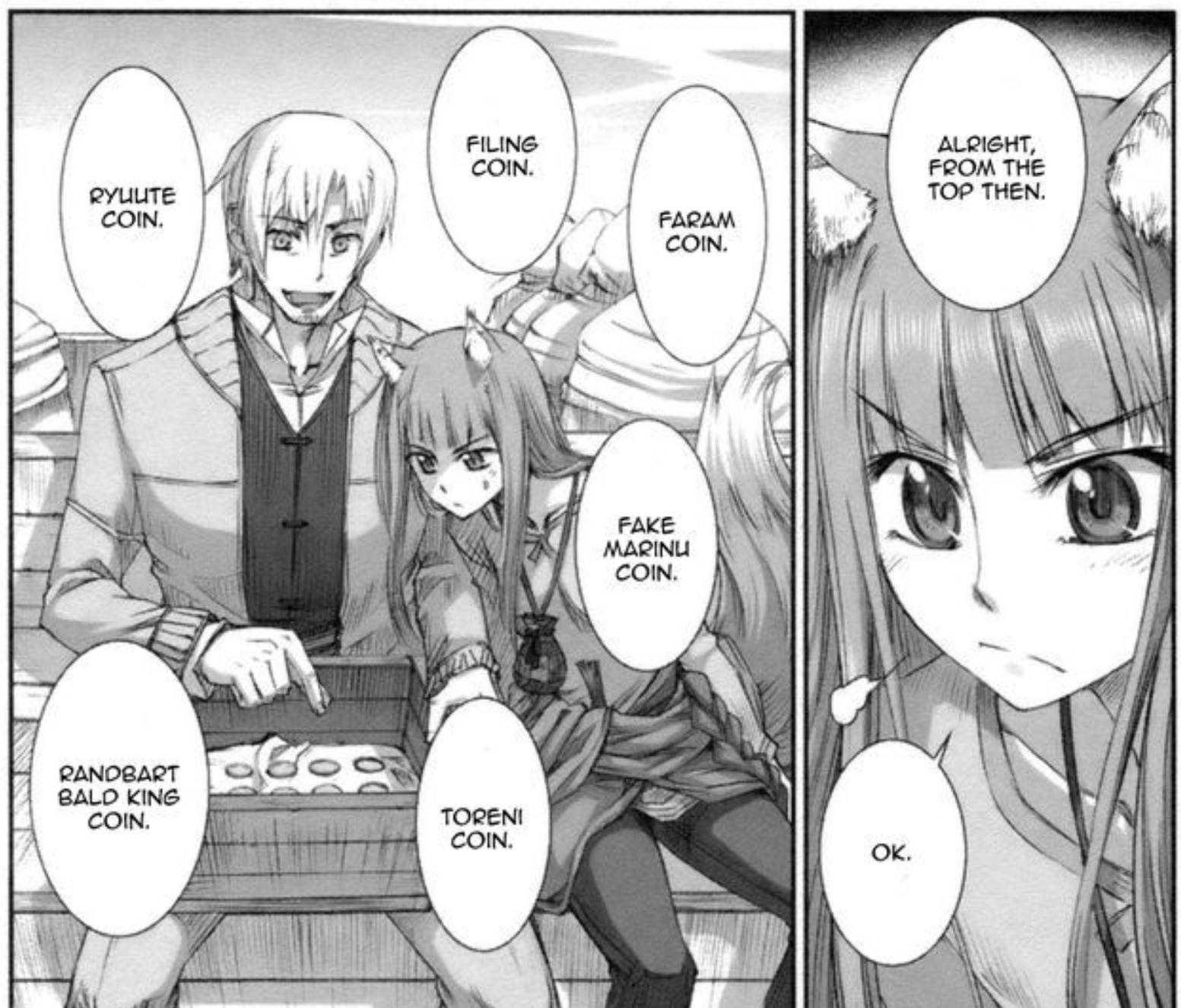

Competition of Coinage

Economic science has put us in a position to understand that competitive coinage is an even better way of preserving the trustworthiness of coins. There is no economic reason not to allow every private citizen to enter the minting business and to offer his own coins.

A private minter too might abuse the trust his customers put in him and his coins. But punishment is immediate: he will lose all his customers. People will start using other coins issued by people they have reason to trust more. On a free market, the money owners can assert this property right smoothly and swiftly. Each person who no longer trusts the minter A simply stops using A’s coins and begins to use the coins of minter B. Thus he leaves the A community and joins the B community.

Competition in coinage is no panacea. Abuses are always possible and in many cases they cannot easily be repaired. The virtue of competition is that it offers the prospect of minimizing the scope of possible abuses. And its great charm is that it involves the entire community of money users, not just some appointed or self-appointed office holders. In a way, this competitive process also fulfills Oresme’s postulate that the entire community of money users decide about coinage.

In Closing

In a free society, the market participants would constantly weigh the advantages and disadvantages of the various certification products. In a free market for money, individuals would choose the currencies they want to use.

This is an abridged version of Jörg Guido Hülsmann’s The Ethics of Money Production. If you’re interested to read more, the original book is available as a free PDF and on paperback.

Extra: Credit Money

There are good reasons to assume that a free society would harbor a variety of different monies, which would all be natural monies in our sense.

Now there are other monies that do not derive their prior value from consumption. The most important cases are paper money and electronic money, to which we will turn below. But there is also credit money. Paper money must not be confused with credit money made out of paper, or with money certificates made out of paper. The latter can be redeemed into commodity money; the former cannot.

Credit money comes into being when financial instruments are being used in indirect exchanges:

Suppose Ben lends 10 oz. of silver to Mike for one year, and that in exchange Mike gives him an IOU (I owe you). Suppose further that this IOU is a paper note with the inscription “I owe to the bearer of this note the sum of 10 oz., payable on January 1, 2010 (signature).” Then Ben could try to use this note as a medium of exchange. This might work if the prospective buyers of the note will also trust Mike’s declaration to pay back the credit as promised. If Mike’s reputation is good with certain people, then it is likely that these people will accept his note as payment for their goods and services. Mike’s IOU then turns into credit money.

Credit money is only a derived kind of money. It receives its value from an expected future redemption into some commodity. In this respect it crucially differs from paper money, which is valued for its own sake. Credit money can never have a circulation that matches the circulation of the natural monies. The reason is that it carries the risk of default. Cash exchanges provide immediate control over the physical money. But the issuer of an IOU might go bankrupt, in which case the IOU would be just a slip of paper.

Extra: Forced Money

Wherever people are not free to choose the best available monies, a different type of money comes into existence — ”forced money.”

In no period of human history, has paper money spontaneously emerged on the free market. The only sure way to bring paper notes into circulation was to impose them on the citizenry. Governments have issued paper money along with the legal obligation for each citizen to accept it as legal tender.

The use of paper money carries the risk of total and permanent value annihilation. This risk does not exist in the case of commodity money, which always carries a positive price and which can therefore always be re-monetized.

In a truly free market, paper money could not withstand the competition of commodity monies. The more farsighted and prudent market participants would get rid of their paper money first, and the others would follow in due course. At the end of this process, which could be consummated in but a few seconds, but which could conceivably also last a few years, the paper currency would be completely eradicated.

📬 Get updates straight to your inbox.

Subscribe to my newsletter so you don't miss new content.